TO: Administrative File: CAG-00447N

FROM: Tamara Syrek Jensen, JD

Director, Coverage and Analysis Group

Joseph Chin, MD, MS

Deputy Director, Coverage and Analysis Group

Lori Ashby, MA

Director, Division of Medical and Surgical Services

Lori Paserchia, MD

Lead Medical Officer

Michelle Issa, MBA

Lead Analyst

SUBJECT: Proposed Decision Memorandum for Screening for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection

DATE: July 7, 2016

I. Proposed Decision

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposes that the evidence is sufficient to conclude that screening for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), consistent with the grade A and B recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of an illness or disability and is appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B, as described below.

Therefore, CMS proposes to cover screening for HBV infection with the appropriate U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved/cleared laboratory tests, used consistent with FDA approved labeling and in compliance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) regulations, when ordered by the beneficiary's primary care physician or practitioner within the context of a primary care setting, and performed by an eligible Medicare provider for these services, for beneficiaries who meet either of the following conditions.

- A screening test would be covered for asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk for HBV infection. "High risk" is defined as persons born in countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection (i.e., ≥ 2%), US-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (i.e., ≥ 8%), HIV-positive persons, men who have sex with men, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection. In addition, CMS proposes that repeated screening would be appropriate annually only for beneficiaries with continued high risk (i.e., men who have sex with men, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection) who do not receive hepatitis B vaccination.

- A screening test at the first prenatal visit is covered for pregnant women. In addition, CMS proposes that repeated screening during the first prenatal visit would be appropriate for each pregnancy, regardless of previous hepatitis B vaccination or previous negative hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test results.

The determination of "high risk for HBV" is identified by the primary care physician or practitioner who assesses the patient's history, which is part of any complete medical history, typically part of an annual wellness visit and considered in the development of a comprehensive prevention plan. The medical record should be a reflection of the service provided.

For the purposes of this proposed decision memorandum, a primary care setting is defined by the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community. Emergency departments, inpatient hospital settings, ambulatory surgical centers, independent diagnostic testing facilities, skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, clinics providing a limited focus of health care services, and hospice are examples of settings not considered primary care settings under this definition.

For the purposes of this proposed decision memorandum, a "primary care physician" and "primary care practitioner" will be defined consistent with existing sections of the Social Security Act (§1833(u)(6), §1833(x)(2)(A)(i)(I) and §1833(x)(2)(A)(i)(II)).

§1833(u)

(6) Physician Defined.—For purposes of this paragraph, the term "physician" means a physician described in section 1861(r)(1) and the term "primary care physician" means a physician who is identified in the available data as a general practitioner, family practice practitioner, general internist, or obstetrician or gynecologist.

§1833(x)(2)(A)(i)

(I) is a physician (as described in section 1861(r)(1)) who has a primary specialty designation of family medicine, internal medicine, geriatric medicine, or pediatric medicine; or

(II) is a nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, or physician assistant (as those terms are defined in section 1861(aa)(5));

CMS is seeking comments on our proposed decision. We will respond to public comments in a final decision memorandum, as required by §1862(l)(3) of the Social Security Act (the Act).

II. Background

Throughout this document we use numerous acronyms, some of which are not defined as they are presented in direct quotations. Please find below a list of these acronyms and corresponding full terminology:

AAFP – American Academy of Family Physicians

AASLD – American Association for the Study for Liver Diseases

ACOG - American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

ACIP - Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

AHRQ – Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

ALT - alanine aminotransferase

AST – aspartate aminotransferase

CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CLIA – Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act

CMS - Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CMV – cytomegalovirus

EBV – Epstein Barr virus

FDA - Food and Drug Administration

HAV – hepatitis A virus

HBc – hepatitis B core antigen

HBeAg – hepatitis B e antigen

HBIG – hepatitis B immune globulin

HBsAg – hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV – hepatitis B virus

HCV – hepatitis C virus

HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma

HIV – human immunodeficiency virus

IDSA – Infectious Disease Society of America

IDU – injection drug user

IFN – interferon

IgM – immunoglobulin M

IOM – Institute of Medicine

MMWR – Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

MSM – men who have sex with men

NCA - National Coverage Analysis

NCD - National Coverage Determination

NNS – number needed to screen

US - United States

USPSTF – United States Preventive Services Task Force

In 2004 the USPSTF first recommended screening for HBV infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit (A recommendation). This recommendation was reaffirmed in 2009. The USPSTF "recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. (This is a grade A recommendation)" (USPSTF 2009). http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-b-in-pregnant-women-screening

In 2014 the USPSTF updated their HBV screening guideline with a focus on asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk for hepatitis B virus infection including those at high risk who were vaccinated before being screened for HBV infection. The USPSTF recommended screening for HBV infection in persons at high risk for infection (B recommendation). Of note, the USPSTF did not define "adolescents." (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014)

CMS initiated this national coverage analysis (NCA) to evaluate the existing evidence for HBV infection screening to consider coverage under the Medicare Program.

The scope of this NCA includes a review of the existing evidence and a determination if the body of evidence is sufficient for Medicare coverage of screening for HBV in Medicare beneficiaries. For the purposes of this NCA, we are furnishing information on viral hepatitis as an inflammation of the liver caused by HBV. Hepatitis arising from other viral agents, e.g. hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV) is not within the scope of this NCA.

Clinical Course

HBV is transmitted by exposure to blood or blood-containing body fluids such as serum, semen, or saliva. HBV infection attacks the liver and leads to inflammation. An infected person may initially develop symptoms such as nausea, anorexia, fatigue, fever, and abdominal pain, or may be asymptomatic. Common signs of acute infection are jaundice and abnormal liver function test results (e.g., increased level of alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) (Chou 2014).

According to Chou et al. (2014), acute HBV infection generally resolves in two to four months. The risk of progression from acute to chronic infection varies according to the age of the person. For those older than five years of age, the risk of progression to chronic infection is less than five percent. Chronic infection can spontaneously resolve however the natural history of chronic infection can vary widely, with some patients transitioning between different phases of chronic infection. As noted by LeFevre (2014), the potential long-term sequelae of chronic infection include cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The estimated mortality rate for persons with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis or HCC is 15% to 25%. Chou et al. (2014) reported that in 2010 there were an estimated 0.5 deaths associated with HBV infection per 100,000

persons, with the highest death rates among persons age 55 to 64 years, persons of "non-white, non-black" race, and males.

Lok et al. (2016) noted that the "natural course of chronic HBV infection consists of four characteristic phases: immune tolerant, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive immune active, inactive, and HBeAg-negative immune active phases. The immune tolerant phase is characterized by the presence of HBeAg, normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, and high levels of HBV DNA, usually well over 20,000 IU/mL. The immune active phases, also called HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis, are characterized by intermittently or persistently elevated ALT with active hepatic inflammation and HBV DNA generally above 2000 IU/mL. The inactive phase is characterized by absence of HBeAg and presence of hepatitis B e antibody, normal ALT in the absence of other concomitant liver diseases, and undetectable or low levels of HBV DNA, generally below 2000 IU/mL. Although not all patients go through each phase and immune responses to HBV during each phase have not been fully characterized, this classification schema provides a useful framework when developing a management approach for chronic HBV infection."

Risk

The USPSTF identified country of origin as the most important risk factor for HBV infection (LeFevre 2014). The CDC declared that countries with a prevalence threshold of ≥ 2% have a high risk for HBV infection (Weinbaum 2008). LeFevre (2014) noted that persons "born in countries with a prevalence of HBV infection of 2% or greater account for 47% to 95% of those with chronic HBV infection in the United States." The CDC estimated the prevalence of HBV infection in the general U.S. population to be 0.3% to 0.5% however certain U.S. groups of people (HIV-positive persons, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of person with HBV infection, and men who have sex with men) have a prevalence of ≥ 2% infection. LeFevre et al. (2014) stated that another important risk factor for HBV infection "is lack of vaccination in infancy in U.S.-born persons with parents from a country or region with high prevalence (≥ 8%), such as sub-Saharan Africa, central and Southeast Asia, and China."

Epidemiology

Lok et al. (2016) noted that the number of people globally with chronic HBV infection increased from 223 million in 1990 to 240 million in 2005. According to Chou et al. (2014), "The reported incidence of acute symptomatic HBV infections in the United States has fallen from over 20,000 cases annually in the mid-1980s to 2,890 cases in 2011. Due to underreporting, the actual number of cases is estimated to be 6.5 times higher than the number of reported cases. From 2000 to 2010, the incidence of acute HBV infection declined among all age groups. In 2010, the highest rate of new HBV infections was among persons age 30 to 39 years (2.33 cases/100,000 population), with males and black persons at highest risk. As of 2008, an estimated 704,000 people in the United States were chronically infected with HBV."

Reducing Incidence and Prevalence of HBV Infections

Key components of a broad program to decrease incidence and prevalence of HBV infections include individual behavioral risk reduction, vaccination and screening. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) stated:

"In settings in which a high proportion of adults have risks for HBV infection (e.g., sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus testing and treatment facilities, drug-abuse treatment and prevention settings, health-care settings targeting services to IDUs, health-care settings targeting services to MSM, and correctional facilities), ACIP recommends universal hepatitis B vaccination for all unvaccinated adults. In other primary care and specialty medical settings in which adults at risk for HBV infection receive care, health-care providers should inform all patients about the health benefits of vaccination, including risks for HBV infection and persons for whom vaccination is recommended, and vaccinate adults who report risks for HBV infection and any adults requesting protection from HBV infection. To promote vaccination in all settings, health-care providers should implement standing orders to identify adults recommended for hepatitis B vaccination and administer vaccination as part of routine clinical services, not require acknowledgment of an HBV infection risk factor for adults to receive vaccine, and use available reimbursement mechanisms to remove financial barriers to hepatitis B vaccination" (Mast 2006).

Medicare provides coverage under Part B for hepatitis B vaccine and its administration, furnished to a Medicare beneficiary who is at high or intermediate risk of contracting hepatitis B. 42 C.F.R. § 410.63.

Screening

HBV is a DNA virus surrounded by a protein capsule (called a core antigen [HBc]) that is then enveloped by another protein (called a surface antigen [HBsAg]) (Chou 2014). HBV screening tests determine the presence and level of these proteins and HBV e antigen (HBeAg; a viral protein secreted by cells infected with HBV) as well as antibodies to these proteins that are circulating in the blood. These blood (a.k.a., serologic) markers are the first tests performed to determine HBV infection status. If serologic tests indicate active infection, subsequent tests are performed to determine the presence and level of circulating HBV DNA (Chou 2014).

The USPTF noted that "Screening for HBV infection could identify chronically infected persons who may benefit from treatment or other interventions, such as surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma." Additionally, a "U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test followed by a licensed, neutralizing confirmatory test for initially reactive results should be used to screen for HBV infection. Testing for antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs) and hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) is also done as part of a screening panel to help distinguish between infection and immunity. Diagnosis of chronic HBV infection is characterized by persistence of HBsAg for at least 6 mo" (LeFevre 2014).

The CDC noted that "Improving the identification and public health management of persons with chronic HBV infection can help prevent serious sequelae of chronic liver disease and complement immunization strategies to eliminate HBV transmission in the United States" (Weinbaum 2008).

Treatment

The decision to treat with an antiviral drug is based on various clinical factors including the HBV DNA level, the degree of liver inflammation as measured by liver function tests and the HBeAg level. The goal of treatment is to sustainably suppress viral replication and reduce liver inflammation to prevent long-term complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (Chou 2014).

There are currently seven antiviral drugs that are FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with HBV: two formulations of interferon (IFN; interferon alfa-2b and pegylated interferon alfa-2a) and five nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (lamivudine, telbivudine, entecavir, adefovir and tenofovir). Pegylated IFN alfa-2a, entecavir or tenofovir are common first-line drugs as monotherapy because of their effectiveness and safety profile (Chou 2014).

Lok et al. (2016) noted that all of the FDA-approved antiviral drugs "suppress viral replication and ameliorate hepatic inflammation but do not eradicate HBV. While IFN is given for a finite duration, nucleos(t)ide analogues are administered for many years and often for life. Long durations of treatment are associated with risks of adverse reactions, drug resistance, nonadherence, and increased cost. Therefore, there is a need to have evidence-based guidelines to help providers determine when treatment should be initiated, which medication is most appropriate, and when treatment can safely be stopped."

ACOG notes that "Newborns born to hepatitis B carriers should receive combined immunoprophylaxis consisting of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth." https://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=12627

III. History of Medicare Coverage

Pursuant to §1861(ddd)(1) of the Social Security Act, CMS may add coverage of "additional preventive services" if certain statutory requirements are met. Our regulations provide:

§410.64 Additional preventive services

(a) Medicare Part B pays for additional preventive services not described in paragraph (1) or (3) of the definition of "preventive services" under §410.2, that identify medical conditions or risk factors for individuals if the Secretary determines through the national coverage determination process (as defined in section 1869(f)(1)(B) of the Act) that these services are all of the following:

(1) Reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

(2) Recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.

(3) Appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B.

(b) In making determinations under paragraph (a) of this section regarding the coverage of a new preventive service, the Secretary may conduct an assessment of the relation between predicted outcomes and the expenditures for such services and may take into account the results of such an assessment in making such national coverage determinations.

Currently, screening for HBV infection is not covered by Medicare.

A. Current Request

CMS received a formal request for a national coverage determination from a coalition of organizations including the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations (AAPCHO), Hep B United, Hepatitis B Foundation, National Task Force on Hepatitis B: Focus on Asian and Pacific Islander Americans, and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable and co-signed by 76 other organizations to consider coverage for screening for HBV infection. The formal request letter can be viewed via the tracking sheet for this NCA on the CMS website at https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-tracking-sheet.aspx?NCAId=283 .

B. Benefit Category

Medicare is a defined benefit program. For an item or service to be covered by the Medicare program, it must fall within one of the statutorily defined benefit categories outlined in the Social Security Act. Since January 1, 2009, CMS is authorized to cover "additional preventive services" if certain statutory requirements are met as provided under §1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act.

IV. Timeline of Recent Activities

| Date |

Action |

| 1/21/2016 |

CMS initiates this national coverage analysis for Screening for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection. A 30-day public comment period begins. |

| 2/20/2016 |

First public comment period ends. CMS receives 50 comments. |

| 7/07/2016 |

Proposed Decision Memorandum posted. 30-day public comment period begins. |

V. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Status

Diagnostic laboratory tests are regulated by the FDA. There are several laboratory tests that can detect the presence of antibodies and antigens produced by the HBV, as well as tests to detect circulating HBV DNA that are FDA approved/cleared and available. The FDA In Vitro Diagnostics database provides specific information on the approved or cleared tests.

VI. General Methodological Principles

When making national coverage determinations concerning additional preventive services, CMS applies the statutory criteria in §1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act and evaluates relevant clinical evidence to determine whether or not the service is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability, is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF, and is appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B of the Medicare program.

Public comments sometimes cite published clinical evidence and give CMS useful information. Public comments that give information on unpublished evidence such as the results of individual practitioners or patients are less rigorous and therefore less useful for making a coverage determination. Public comments that contain personal health information will not be made available to the public. CMS responds in detail to the public comments on a proposed national coverage determination when issuing the final national coverage determination.

VII. Evidence

A. Introduction

Consistent with §1861(ddd)(1)(A) and 42 CFR § 410.64(a)(1), additional preventive services must be reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability. With respect to evaluating whether screening tests conducted on asymptomatic individuals are reasonable and necessary for these purposes, the analytic framework involves consideration of different factors compared to either diagnostic tests or therapeutic interventions. Evaluation of screening tests has been largely standardized in the medical and scientific communities, and the "value of a screening test may be assessed according to the following criteria:

- Simplicity. In many screening programmes more than one test is used to detect one disease, and in a multiphasic programme the individual will be subjected to a number of tests within a short space of time. It is therefore essential that the tests used should be easy to administer and should be capable of use by para-medical and other personnel.

- Acceptability. As screening is in most instances voluntary and a high rate of co-operation is necessary in an efficient screening programme, it is important that tests should be acceptable to the subjects.

- Accuracy. The test should give a true measurement of the attribute under investigation.

- Cost. The expense of screening should be considered in relation to the benefits resulting from the early detection of disease, i.e., the severity of the disease, the advantages of treatment at an early stage and the probability of cure.

- Precision (sometimes called repeatability). The test should give consistent results in repeated trials.

- Sensitivity. This may be defined as the ability of the test to give a positive finding when the individual screened has the disease or abnormality under investigation.

- Specificity. This may be defined as the ability of the test to give a negative finding when the individual screened does not have the disease or abnormality under investigation" (Cochran and Holland 1971).

As Cochrane and Holland (1971) noted, evidence on health outcomes, i.e., "evidence that screening can alter the natural history of disease in a significant proportion of those screened," is important in the consideration of screening tests since individuals are asymptomatic and "the practitioner initiates screening procedures" (Cochran and Holland 1971).

Four of the seven criteria cited above (Cochrane and Holland 1971) as reasonable and necessary for screening tests (i.e., accuracy, precision, sensitivity and specificity) reflect a screening test's ability to minimize the harm of testing inaccuracy, especially from false positive or false negative results.

Primary Care and USPSTF Recommended Preventive Services

The USPSTF functions as an independent panel of non-Federal experts in prevention and primary care. The USPSTF Procedure Manual can be found at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/methods-and-processes.

Many preventive services are discussed within the context of the primary care setting and the USPSTF reviews preventive services that should be provided in the primary care setting. Primary care providers are thought of as the initial contact for patients within a complicated health system. Primary care providers are often identified as the conduit for identifying the need for preventive services by assessing the patient's individual risk factors and developing a comprehensive prevention plan that directs patients in a coordinated manner to appropriate services to address their individual health risks and provide the most efficient utilization of health care services.

USPSTF Grade Definitions

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) assigns one of five letter grades to each of its recommendations (A, B, C, D, I). In July of 2012, the grade definitions were updated to reflect the change in definition of and suggestions for practice for the grade C recommendation.

The following tables from the USPSTF website provide the current grade definitions and descriptions of levels of certainty. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm)

Grade Definitions After July 2012

| Grade |

Definition |

Suggestions for Practice |

| A |

The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

Offer or provide this service. |

| B |

The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net

benefit is moderate to substantial. |

Offer or provide this service. |

| C |

The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

Offer or provide this service for selected patients depending on individual circumstances. |

| D |

The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

Discourage the use of this service. |

| I Statement |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is

lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

Read the clinical considerations section of USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms. |

Level of Certainty |

Description |

| High |

The available evidence usually includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations. These studies assess the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes. This conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies. |

| Moderate |

The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by such factors as:

The number, size, or quality of individual studies.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Limited generalizability of findings to routine primary care practice.

Lack of coherence in the chain of evidence.

As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this change may be large enough to alter the conclusion. |

| Low |

The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of:

The limited number or size of studies.

Important flaws in study design or methods.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Gaps in the chain of evidence.

Findings not generalizable to routine primary care practice.

Lack of information on important health outcomes.

More information may allow estimation of effects on health outcomes. |

* The USPSTF defines certainty as "likelihood that the USPSTF assessment of the net benefit of a preventive service is correct." The net benefit is defined as benefit minus harm of the preventive service as implemented in a general, primary care population. The USPSTF assigns a certainty level based on the nature of the overall evidence available to assess the net benefit of a preventive service.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for HBV

"The USPSTF recommends screening for HBV infection in persons at high risk for infection. (B recommendation)."

(http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014)

"The USPSTF recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. (This is a grade A recommendation)."

(http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-b-in-pregnant-women-screening)

The evidence supporting these recommendations is considered and summarized in section VII.B3 of this document.

B. Discussion of Evidence

This section provides a summary of the evidence we considered during our review. The evidence reviewed includes the published medical literature concerning HBV infection in asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults as well as in pregnant women. Our discussion focuses upon the adequacy of the evidence to draw conclusions about the risks and benefits of screening for HBV for Medicare patients, in other words, for those beneficiaries who are 65 years old and older and for those who are on Medicare disability or in the End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) program.

CMS searches for and considers literature articles, reports and guidelines that present evidence rather than present a review or a commentary. This evidence usually concerns clinical health outcomes associated with screening for HBV infection that typically are objective in nature, such as mortality and adverse event rates. Consequently, studies that evaluate screening test strategies are not as relevant and are less helpful to CMS. Lastly, when evaluating "additional preventive services," CMS may conduct an assessment of the relation between predicted outcomes and the expenditures for the service. §1861(ddd)(2); 42 C.F.R. §410.64(b).

1. Evidence Question(s)

The questions of interest for this national coverage analysis are:

1a. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF?

1b. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability?

1c. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is appropriate for Medicare beneficiaries?

2. External Technology Assessments

CMS did not request an external technology assessment (TA) on this issue.

3. Internal Technology Assessment

Literature Search Methods

In addition to the prerequisite USPSTF recommendations, CMS must consider not only whether an additional preventive service is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability, but whether the service is appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under part A or enrolled under part B of the Medicare program.

CMS performed a literature search using PubMed on March 15, 2016 with the search terms "screening," "hepatitis b virus" and "human." The following limitations were applied: English and a publication date from January 1, 2014 to March 15, 2016. The earlier date of this publication date range represented the end date for the most recent literature review performed by an AHRQ technology assessment (Chou 2014). No citation was found that presented the results of a clinical study in which HBV screening was an intervention, rather than an outcome.

CMS included in the evidence section the most recent screening recommendations from the USPSTF for pregnant women (USPSTF 2009) and for nonpregnant adolescents and adults (LeFevre 2014). Relevant citations from the USPSTF (2009) and LeFevre (2014) articles were included in the evidence section (Lin 2009; Chou 2014; Weinbaum 2008; Lok 2009). Lin (2009) presented a technology assessment of screening during pregnancy that was performed by AHRQ. Chou (2014) presented a technology assessment funded by AHRQ. Weinbaum (2008) presented the recommendations of the CDC. Lok (2009) presented an AASLD practice guideline.

A second search was performed on March 15, 2016 using the search terms "hepatitis b virus," "screening," "human," and "cost effectiveness." The publication date range was January 1, 2006 to March 15, 2016. No relevant studies on cost-effectiveness were found.

Public comments that included a list of citations were reviewed. No new evidence was found.

Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults

Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: A systematic review to update the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Annuals of Internal Medicine 2014;161:31.

This article provided a synopsis of a systematic review prepared for the USPSTF by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center/Oregon Health & Science University/Portland, Oregon, which was under contract to AHRQ. The full report of this systematic review is found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK208504/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK208504.pdf.

The authors performed a systematic review based on evidence obtained after a search of MEDLINE (1946 to January 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsycINFO and reference lists of retrieved articles. The analytic framework focused on "direct evidence that screening for HBV infection improves important health outcomes versus not screening and the chain of indirect evidence linking screening to improved health outcomes" for nonpregnant adults and adolescents. The three screening-related key questions focused on determining the benefits and harms of screening for HBV infection versus no screening in asymptomatic adolescents and adults and determining the screening strategies to identify persons with HBV infection.

Study selection inclusion criteria limited the review to evidence from randomized trials and observational studies in asymptomatic adults with no known abnormal liver function tests. Relevant exclusion criteria included non-English-language articles, studies published only as abstracts, studies of patients co-infected with HIV or HCV, studies of transplant recipients and studies of patients receiving hemodialysis.

The quality of each study was rated as "good," "fair," or "poor" using criteria developed by the USPSTF. In addition, for each key question the authors assessed the internal validity of the evidence as "good," "fair," or "poor" based on the number, quality and size of studies as well as the consistency of the results and the directness of the evidence using criteria developed by the USPSTF.

The authors did not find any studies that addressed the key questions concerning the benefits and harms of screening for HBV infection versus no screening in asymptomatic adolescents and adults.

With regards to screening strategies to identify persons with HBV infection, the authors stated that "One fair-quality cross-sectional study (n = 6194) done in a French clinic for sexually transmitted infections found that targeted screening of persons born in countries with a prevalence of chronic HBV infection of 2% or greater, men, and unemployed persons identified 98% (48 of 49) of infections while testing approximately two thirds of patients, for an NNS of 82 to identify 1 case of HBV infection. Screening based on behavioral risk factors, such as injection drug use and high-risk sexual behaviors, resulted in a higher NNS and did not improve sensitivity. Screening only persons born in countries with a higher prevalence for HBV infection missed two thirds of infections (sensitivity, 31%), with an NNS of 16."

The authors listed a number of limitations of their systematic review including the exclusion of non-English-language articles; the inability to formally assess publication bias due to the small number of studies; and the inclusion of studies done in countries where the prevalence, characteristics, and natural history of HBV infection were different from those of the United States, which potentially limited the applicability of those studies’ results to screening in the United States.

The authors noted that similar to the 2004 USPSTF review, "we found no direct evidence on effects of screening for HBV infection versus no screening on clinical outcomes. The USPSTF previously determined that standard serologic markers are accurate for diagnosing HBV infection.

Evidence on the usefulness of different screening strategies for identifying persons with HBV infection was limited to a single fair-quality, cross-sectional study. It identified a relatively efficient screening strategy based on country of origin, sex, and employment status but was done in a French clinic for sexually transmitted infections and had limited applicability to primary care settings in the United States."

Chou et al. further noted that "Additional research may clarify the benefits and harms of screening for HBV infection. Studies that compare clinical outcomes in persons screened and not screened for HBV infection would require large samples and long follow-up. In lieu of such direct evidence, prospective studies on the accuracy and yield of alternative screening strategies (such as those targeting immigrants from countries with a high prevalence of HBV infection) could help identify optimal screening strategies."

The authors concluded that "screening can identify persons with chronic HBV infection, and antiviral treatment is associated with improved intermediate outcomes. However, research is needed to better define the effects of screening and subsequent interventions on clinical outcomes and to identify optimal screening strategies. The declining incidence and prevalence of HBV infection as a result of universal vaccination will probably affect future assessments of screening."

LeFevre ML, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2014;161:58. (Summary for USPSTF Recommendation for Screening)

In this article, the USPSTF presented its recommendation statement that "applies to asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk for HBV infection (including those at high risk who were vaccinated before being screened for HBV infection." The USPSTF recommended screening for HBV infection in persons at high risk for infection (B recommendation). The USPSTF concluded that:

"Identification of chronic HBV infection based on serologic markers is considered accurate."

"The USPSTF found no randomized, controlled trials that provide direct evidence of the health benefits (that is, reduction in morbidity, mortality, and disease transmission) of screening for HBV infection in asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults."

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence that HBV vaccination is effective at decreasing disease acquisition."

"The USPSTF found convincing evidence that antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection is effective at improving intermediate outcomes (that is, virologic or histologic improvement or clearance of hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg]) and adequate evidence that antiviral regimens improve health outcomes (such as reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma). The evidence showed an association between improvement in intermediate outcomes after antiviral therapy and improvement in clinical outcomes, but outcomes were heterogeneous and the studies had methodological limitations."

"The USPSTF found inadequate evidence that education or behavior change counseling reduces disease transmission."

"The prevalence of HBV infection differs among various populations. As a result, the magnitude of benefit of screening varies according to risk group."

"The USPSTF concludes that screening is of moderate benefit for populations at high risk for HBV infection, given the accuracy of the screening test and the effectiveness of antiviral treatment."

"The USPSTF found inadequate evidence on the harms of screening for HBV infection. Although evidence to determine the magnitude of harms of screening is limited, the USPSTF considers these harms to be small to none."

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence that antiviral therapy regimens are associated with a higher risk for withdrawal due to adverse events than placebo. However, trials found no difference in the risk for serious adverse events or the number of participants who had any adverse event. In addition, most antiviral adverse events were self-limited with discontinuation of therapy. The USPSTF found adequate evidence that the magnitude of harms of treatment is small to none."

"The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for HBV infection in persons at high risk for infection has moderate net benefit."

The USPTF noted that "Important risk groups for HBV infection with a prevalence of ≥ 2% that should be screened include:

- Persons born in countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection (≥ 2%)

- US-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥ 8%), such as sub-Saharan Africa and central and Southeast Asia

- HIV-positive persons

- Injection drug users

- Men who have sex with men

- Household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection"

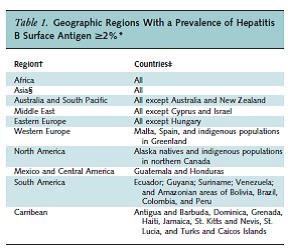

Leferve et al. Table 1. Annals of Internal Medicine 2014;161:58.

The USPTF noted that "periodic screening may be useful in patients with ongoing risk for HBV transmission" and that "clinical judgment should determine screening frequency, because the USPTF found inadequate evidence to determine specific screening intervals."

Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. CDC MMWR September 19, 2008. Vol. 57, No. RR-8, pages 1 - 20.

This 2008 report presented the CDC's recommendation and expanded its previous HBV testing guidelines. In 2007 the CDC convened a team of experts in the prevention, care and treatment of chronic HBV from within and outside the Federal Government. This team "reviewed available published and unpublished epidemiologic and treatment data, considered whether to recommend testing specific new populations for HBV infection, and discussed how best to implement new and existing testing strategies. Topics discussed included 1) the changing epidemiology of chronic HBV infection, 2) health disparities caused by the disproportionate HBV-related morbidity and mortality among persons infected as infants and young children in countries with high levels of HBV endemicity, and 3) the increasing benefits of care and opportunities for prevention for infected persons and their contacts. On the basis of this discussion, CDC determined that reconsideration of current guidelines was warranted."

CDC recommended testing for the following populations:

- "Persons born in regions of high and intermediate HBV endemicity (HBsAg prevalence >2%)"

- "U.S.-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with high HBV endemicity (>8%)"

- "Injection-drug users"

- "Men who have sex with men"

- "Persons needing immunosuppressive therapy, including chemotherapy, immunosuppression related to organ transplantation, and immunosuppression for rheumatologic or gastroenterologic disorders"

- "Persons with elevated ALT/AST of unknown etiology"

- "Donors of blood, plasma, organs, tissues, or semen"

- "Hemodialysis patients"

- "All pregnant women"

- "Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers"

- "Household, needle-sharing, or sex contacts of persons known to be HBsAg positive"

- "Persons who are the sources of blood or body fluids for exposures that might require postexposure prophylaxis (e.g., needlestick, sexual assault)"

- "HIV-positive persons"

All Pregnant Women

Lin K and Vickery J. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009;150:874.

This article provided a synopsis of a systematic review prepared for the USPSTF by AHRQ. The authors performed a systematic review based on evidence obtained after a literature search (January 2001 to March 2008) and reference lists of retrieved articles. The goal of this "reaffirmation update was to search for large, high-quality studies related to HBV screening in pregnancy that have been published since the 2004 USPSTF recommendation." The key questions focused on determining the benefits and harms of screening for HBV infection.

The authors did not find any new randomized, controlled studies that addressed the key questions. The authors concluded that "No new evidence was found on the benefits or harms of screening for HBV infection in pregnant women. Previously published randomized trials support the 2004 USPSTF recommendation for screening."

USPSTF 2009. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. Annuals of Internal Medicine 2009;150:869.

In this article, the USPSTF presented its recommendation statement, which applies to all pregnant women. The USPSTF "recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. (This is a grade A recommendation)." The USPSTF determined that:

- "USPSTF found no new substantial evidence that could change its recommendation and, therefore, reaffirms its recommendation to screen pregnant women for hepatitis B at their first prenatal visit."

- "USPSTF found no published studies that describe harms of screening for HBV infection in pregnant women. The USPSTF concluded that the potential harms of screening are no greater than small."

- "USPSTF found convincing evidence that universal prenatal screening for HBV infection substantially reduces perinatal transmission of HBV and the subsequent development of chronic HBV infection. The current practice of vaccinating all infants against HBV infection and providing postexposure prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin administered at birth to infants of mothers infected with HBV substantially reduces the risk for acquiring HBV infection."

The USPSTF concluded that "there is high certainty that the net benefit of screening pregnant women for HBV infection is substantial."

The USPTF noted that "A test for HBsAg should be ordered at the first prenatal visit with other recommended screening tests. At the time of admission to a hospital, birth center, or other delivery setting, women with unknown HBsAg status or with new or continuing risk factors for HBV infection (such as injection drug use or evaluation or treatment for a sexually transmitted disease) should receive screening."

The USPSTF also noted that "Screening for HBV infection by testing for HBsAg should be performed in each pregnancy, regardless of previous hepatitis B vaccination or previous negative HBsAg test results."

Cost-effectiveness of HBV Screening

No relevant studies were found.

4. Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC)

A MEDCAC meeting was not convened on this issue.

5. Evidence-Based Guidelines

A number of evidence-based guidelines were identified.

USPSTF

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for HBV (see summary of the LeFevre 2014 article and the USPSTF 2009 article above).

CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for Identification and Public Health Management of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection (see summary of the Weinbaum 2008 article above).

American Association for the Study for Liver Diseases (AASLD)

In an update to its practice guideline for the management of chronic hepatitis B, which was endorsed by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), the AASLD (Lok 2009) recommended that the following persons should be tested:

- persons born in high or intermediate endemic areas,

- persons born in the U.S. who were not vaccinated as infants and whose parents were born in regions with high HBV endemicity,

- persons with chronically elevated aminotransferases,

- persons needing immunosuppressive therapy,

- men who have sex with men,

- persons with multiple sexual partners or history of sexually transmitted disease,

- inmates of correctional facilities,

- persons who have ever used injecting drugs,

- dialysis patients,

- HIV or HCV-infected individuals,

- pregnant women, and

- family members, household members, and sexual contacts of HBV-infected persons

Testing for HBsAg and anti-HBs should be performed, and seronegative persons should be vaccinated.

AASLD classifies the following groups as high risk for HBV infection:

- "Individuals born in areas of high* or intermediate prevalence rates† for HBV including immigrants and adopted children‡§

—Asia: All countries

—Africa: All countries

—South Pacific Islands: All countries

—Middle East (except Cyprus and Israel)

—European Mediterranean: Malta and Spain

—The Arctic (indigenous populations of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland)

—South America: Ecuador, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, and Amazon regions of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Peru

—Eastern Europe: All countries except Hungary

—Caribbean: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Granada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and Turks and Caicos

—Central America: Guatemala and Honduras

- Other groups recommended for screening

—U.S. born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with high HBV endemicity (≥8%)

—Household and sexual contacts of HBsAg-positive persons§

—Persons who have ever injected drugs§

—Persons with multiple sexual partners or history of sexually transmitted disease§

—Men who have sex with men§

—Inmates of correctional facilities§

—Individuals with chronically elevated ALT or AST§

—Individuals infected with HCV or HIV§

—Patients undergoing renal dialysis§

—All pregnant women

—Persons needing immunosuppressive therapy

*HBsAg prevalence 8%.

†HBsAg prevalence 2% - 7%.

‡If HBsAg-positive persons are found in the first generation, subsequent generations should be tested.

§Those who are seronegative should receive hepatitis B vaccine."

Regarding the quality of evidence rating for this recommendation, AASLD assigned a grade of "I," where "I" stands for "Randomized controlled trials."

6. Professional Society Recommendations / Consensus Statements / Other Expert Opinion

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

In its clinical preventive service recommendation statement for HBV infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults (accessed on March 29, 2016 at http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/hepatitis.html), the AAFP stated: "The AAFP recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in persons at high risk for infection. (2014)" This is a Grade B recommendation and AAFP cited the USPSTF recommendations for HBV as the evidentiary source for their recommendation.

For pregnant women, "AAFP recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. (2009)" This is a Grade A recommendation and AAFP cited the USPSTF recommendations for HBV as the evidentiary source for their recommendation.

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

ACOG recommends routine prenatal screening of all pregnant women by hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) testing. This is a Level A recommendation, which signifies that the recommendations was "based on good and consistent scientific evidence." https://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=12627.

7. Public Comment

Public comments sometimes cite the published clinical evidence and give CMS useful information. Public comments that give information on unpublished evidence such as the results of individual practitioners or patients are less rigorous and therefore less useful for making a coverage determination.

Initial Comment

During the initial 30-day public comment period (1/21/2016 - 2/20/2016), CMS received 50 comments from various entities including providers, advocacy organizations, trade associations, and the general public. Of the comments received, 49 commenters advocated for coverage of screening for HBV infection, and 1 commenter did not express a position.

The comments received during the initial 30-day public comment period can be viewed in their entirety on the CMS Website at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-view-public-comments.aspx?NCAId=283.

VIII. CMS Analysis

National coverage determinations (NCDs) are determinations by the Secretary with respect to whether or not a particular item or service is covered nationally under title XVIII of the Social Security Act. §1869(f)(1)(B). In order to be covered by Medicare, an item or service must fall within one or more benefit categories contained within Part A or Part B, and must not be otherwise excluded from coverage. Since January 1, 2009, CMS is authorized to cover "additional preventive services" (see Section III above) if certain statutory requirements are met as provided under §1861(ddd)(1) of the Social Security Act. Our regulations at 42 CFR 410.64 provide:

(a) Medicare Part B pays for additional preventive services not described in paragraph (1) or (3) of the definition of "preventive services" under §410.2, that identify medical conditions or risk factors for individuals if the Secretary determines through the national coverage determination process (as defined in section 1869(f)(1)(B) of the Act) that these services are all of the following:

(1) Reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

(2) Recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Service Task Force.

(3) Appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under part A or enrolled under Part B.

(b) In making determinations under paragraph (a) of this section regarding the coverage of a new preventive service, the Secretary may conduct an assessment of the relation between predicted outcomes and the expenditures for such services and may take into account the results of such an assessment in making such national coverage determinations.

CMS notes that any effect of the use of these screening tests is their coordination with treatment. CMS concludes that FDA approval or clearance of screening tests used consistent with FDA approved labeling provides a greater likelihood that a potential harm of screening testing, that is, taking action based on inaccurate screening test results, can be avoided. We further conclude that compliance by testing laboratories with CLIA regulatory requirements provides an additional, on-going safeguard for screening test quality. CMS considers these conditions essential to maximize patient safety.

In addition, CMS acknowledges that the USPSTF is charged with conducting rigorous reviews of scientific evidence to create evidence-based recommendations for preventive services that should be provided by primary care physicians and practitioners in primary care settings. In addition, the USPSTF Procedure Manual outlines the process for evaluating the quality and strength of the evidence for a service, determining the net health benefit (benefits minus harms) associated with the service, and judging the level of certainty that providing these services will be beneficial in primary care.

Evidence for Screening for HBV

An acute HBV infection may become a chronic infection and progress to serious and potentially life-threatening complications including cirrhosis, liver failure, HCC and death. Chou et al. (2014) reported that the estimated mortality rate for persons with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis or HCC is 15% to 25% with the highest death rates among persons age 55 to 64 years, persons of "non-white, non-black" race and males. An estimated 704,000 people in the U.S. were chronically infected with HBV as of 2008 (Chou 2014).

Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults

CMS notes that a recent systematic review of the benefits and harms of HBV screening versus no screening in asymptomatic, nonpregnant U.S. adults and adolescents did not find evidence to directly link HBV screening with any health outcomes of importance to CMS (Chou 2014). However, the authors of this systematic review did find evidence that HBV screening and subsequent treatment of patients with chronic HBV infection with antiviral drugs is associated with improved intermediate outcomes. These findings informed the USPTF position that there is an indirect link in that "convincing evidence that antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection is effective at improving intermediate outcomes (that is, virologic or histologic improvement or clearance of hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg]) and adequate evidence that antiviral regimens improve health outcomes (such as reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma)." The subsequent conclusions and recommendations of the USPSTF are based on the presence of this indirect link (LeFevre 2014) and are supported by the CDC (Weinbaum 2008) as well as a number of evidence-based guidelines from professional societies (Lok 2009; AAFP 2014). CMS notes however that none of these organizations address the applicability of these findings specifically to the majority of Medicare beneficiaries, which is persons 65 years of age or older. Nonetheless, given that there is an estimated 700,000 to 2.2 million people in the U.S. with chronic HBV infection (LeFevre 2014), the implementation of screening to identify HBV-positive persons followed by the prompt administration of antiviral treatment stands to significantly impact health outcomes.

All Pregnant Women

CMS notes that the USPSTF recently reconfirmed its 2004 recommendation to screen for HBV infection in all pregnant women (USPSTF 2009). This reconfirmation was accomplished after commissioning a systematic review by AHRQ that searched for large, high-quality studies related to HBV screening in pregnancy that have been published since the 2004 USPSTF recommendation with the goal of determining the benefits and harms of screening for HBV infection (Lin 2009). The authors did not find new evidence regarding the benefits or harms of screening for HBV infection in pregnant women but noted that "previously published randomized trials support the 2004 USPSTF recommendation for screening" (Lin 2009). These findings informed the USPTF position that there is "convincing evidence that universal prenatal screening for HBV infection substantially reduces perinatal transmission of HBV and the subsequent development of chronic HBV infection," which led the USPSTF to conclude that "there is high certainty that the net benefit of screening pregnant women for HBV infection is substantial" (USPSTF 2009). The USPSTF recommendation is supported by the CDC (Weinbaum 2008) as well as a number of evidence-based guidelines from professional societies (Lok 2009; AAFP 2014; ACOG 2007). CMS notes that the applicability of these findings is only to the small portion of the disabled Medicare beneficiary population. Nonetheless, given that there is an estimated 700,000 to 2.2 million people in the US with chronic HBV infection (LeFevre 2014), the implementation of screening to identify HBV-positive persons followed by the prompt administration of antiviral treatment stands to significantly impact health outcomes.

CMS acknowledges that there are real and potential harms associated with screening for HBV. These harms include anxiety and a decreased quality of life due to the knowledge of disease with the possibility of disease progression to liver failure, cancer and even death. Additional harms are known to be associated with subsequent procedures performed to assess the clinical status of infection, although these harms are most often associated with invasive procedures that are less commonly in use. While side effects during antiviral treatment are associated with an increased risk of early discontinuation of treatment, studies do not indicate an increased risk for serious side effects compared to placebo (Chou 2014).

In general, tests do not directly exert an inherent therapeutic effect. In this case, the improved outcomes for beneficiaries infected with hepatitis B accrue from the use of the test result to inform the subsequent use of therapies and not as a direct result of the act of testing. Thus we look for evidence establishing that the beneficiary's treating physician/practitioner uses a test result to recommend treatments that improve clinically meaningful health outcomes. We recognize that the avoidance of futile and harmful treatments may contribute to improved health outcomes.

The questions of interest for this national coverage analysis are:

1a. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF?

Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults

"The USPSTF concludes that persons at high risk for infection should be screened for HBV infection. (Grade: B recommendation)."

CMS concludes that screening for HBV infection in all persons at high risk for infection is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF.

All Pregnant Women

"The USPSTF recommends screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit. (This is a grade A recommendation)."

CMS concludes that screening for HBV infection in all pregnant women is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF.

1b. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability?

Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults

CMS notes that the USPSTF concluded "with moderate certainty" that HBV screening in asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk for infection has "moderate net benefit" (LeFevre 2014). However, the USPSTF was less certain regarding the frequency of screening due to "inadequate evidence to determine specific screening intervals." Consequently the USPSTF stated that "periodic screening may be useful in patients with ongoing risk for HBV transmission" and concluded that screening frequency should be determined by "clinical judgment" (LeFevre 2014). Neither the CDC nor the clinically-based guidelines from the professional societies addressed the issue of screening frequency in this particular population. In general, screening is only recommended if treatment of the disease at an earlier stage is more beneficial, in terms of health outcomes, than at a later stage (Wilson and Jungner 1968). Since the USPSTF recommendation and CDC evidence-based guidelines recommend screening for hepatitis B for individuals at high risk of infection, it is implicit that an appropriate treatment is available for these individuals. Since there is no definitive guidance on the frequency of screening for the high risk population, CMS has determined that repeated screening would be appropriate annually for beneficiaries with continued high risk (i.e., men who have sex with men, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection) who do not receive hepatitis B vaccination.

After careful review of the available body of evidence, we conclude that screening for HBV infection in all persons at high risk for infection is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

All Pregnant Women

CMS notes that the USPSTF concluded that "there is high certainty that the net benefit of screening pregnant women for HBV infection is substantial" (USPSTF 2009). The USPSTF recommended that "a test for HBsAg should be ordered at the first prenatal visit with other recommended screening tests. At the time of admission to a hospital, birth center, or other delivery setting, women with unknown HBsAg status or with new or continuing risk factors for HBV infection (such as injection drug use or evaluation or treatment for a sexually transmitted disease) should receive screening." In addition, the USPSTF was specific regarding the frequency of screening in that "testing for HBsAg should be performed in each pregnancy, regardless of previous hepatitis B vaccination or previous negative HBsAg test results" (USPSTF 2009). CMS notes that the CDC also recommends screening for hepatitis B infection in all pregnant women (Weinbaum 2008) as does AASLD (Lok 2009), AAFP (2014) and ACOG (2007). Since there is definitive guidance from USPSTF on the frequency of screening for pregnant women, CMS has determined that repeated screening would be appropriate at the first prenatal visit for each pregnancy, regardless of previous hepatitis B vaccination or previous negative HBsAg test results.

After careful review of the available body of evidence, we conclude that screening for HBV infection in pregnant women is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

1c. Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for HBV infection is appropriate for Medicare beneficiaries?

Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults

The 2014 USPSTF recommendation focuses on asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at high risk for HBV infection (including those at high risk who were vaccinated before being screened for HBV infection (LeFevre 2014). The USPSTF did not define "adolescents."

LeFevre et al. (2014) stated that the most important risk factor for HBV infection is country of origin. The CDC declared that countries with a HBV infection prevalence of ≥2% are at high risk (Weinbaum 2008). In addition, the CDC noted that certain U.S. subpopulations (HIV-positive persons, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of a person with HBV infection, and men who have sex with men) also have a prevalence of ≥2% infection and thus are in the high risk category (Weinbaum 2008).

The USPSTF (LeFevre 2014) concluded that the following persons are at "high risk" for HBV infection and should be screened:

- Persons born in countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection (≥ 2%)

- US-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥ 8%), such as sub-Saharan Africa and central and Southeast Asia

- HIV-positive persons

- Injection drug users

- Men who have sex with men

- Household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection

All Pregnant Women

The 2009 USPSTF recommendation focuses on pregnant women. The USPSTF did not define an age range for "women" nor did the USPSTF (2009) focus on risk factors or other specific patient characteristics. Instead, the recommendation applies to all pregnant women. The CDC (Weinbaum 2008), AASLD (Lok 2009), AAFP (2014) and ACOG (2007) statements follow accordingly.

The Part B Medicare beneficiary population is largely comprised of persons aged 65 years and older while a smaller percentage of the beneficiary population is comprised of the disabled, and those persons in the ESRD program. We note that the USPSTF recommendations for this screening preventive service are based on either risk factors or pregnancy status and therefore would be applicable to any Medicare beneficiary who is an adolescent or adult.

Overall

CMS believes that the screening for HBV infection provides an opportunity for appropriate interventions to benefit the infected person by permitting for the early detection of, and potentially the prevention of, HBV-related liver disease. While the USPSTF, CDC and professional societies do not specifically address the various aspects of screening for the 65 year old and older population, CMS believes that the results are generalizable to high risk individuals who are disabled and/or 65 years and older.

After careful review of the available body of evidence, we conclude that screening for HBV infection is appropriate for high risk Medicare beneficiaries who are disabled or 65 years and older. High risk is defined as:

- Persons born in countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection (≥2%);

- U.S.-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥8%), such as sub-Saharan Africa and central and Southeast Asia;

- HIV-positive persons;

- Injection drug users;

- Men who have sex with men;

- Household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection.

We recognize that various professional societies have differing definitions of high risk but we did not find sufficient evidence on health outcomes to expand the high risk definition beyond the population with established risk, consistent with the USPSTF (LeFevre 2014).

Hepatitis B Vaccination

CMS encourages appropriate hepatitis B vaccination. Medicare provides coverage under Part B for hepatitis B vaccine and its administration, furnished to a Medicare beneficiary who is at high or intermediate risk of contracting hepatitis B. 42 C.F.R. 410.63.

Primary Care and USPSTF Recommended Preventive Services

CMS believes the primary care setting and the primary care provider are integral in the coordination of preventive services. The USPSTF creates evidence-based recommendations for preventive services that should be provided in the primary care setting by evaluating the quality and strength of the evidence for a service, determining the net health benefit (benefits minus harms) associated with the service, and judging the level of certainty that providing these services will be beneficial in primary care (2012 USPSTF Clinical Preventive Services Guide).

CMS believes that preventive services should be provided within the context of a coordinated prevention plan based on the individual patient's needs assessed over time through the ongoing relationship established with the primary care provider. The IOM provides a definition of primary care (IOM. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era 1996) and existing sections of the Social Security Act (§1833(u)(6), §1833(x)(2)(A)(i)(I) and §1833(x)(2)(A)(i)(II)) define primary care practitioners. The IOM further identifies one of the values of primary care as the opportunity for disease prevention and health promotion.

Based on the charge of the USPSTF in evaluating services provided in the primary care setting, CMS concludes referrals for the USPSTF recommended screenings for HBV for the specific populations should be ordered by the beneficiary's primary care provider in the primary care setting. CMS also believes that the IOM definition of primary care and the role of primary care in disease prevention and health promotion certainly supports that the risk assessment and referral for these screening services is best coordinated by the primary care provider in the primary care setting.

CMS concludes that the integrated and efficient utilization of these screening tests are best coordinated by the beneficiary's primary care provider and based on an evaluation of the patient risk factors and the appropriate referral and/or initiation of treatment. We are not indicating that the test itself must be performed by a primary care practitioner.

Disparities in HBV

"Improving health care disparities is an integral part of improving health care quality" (AHRQ Healthcare Disparities Report, 2008).

Despite the overall success in the public health campaign against viral hepatitis, "there remain racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the incidence and prevalence of acute and chronic viral hepatitis, the outcomes of chronic viral hepatitis, and health care access and quality" (El-Serag 2010). As noted by Chou et al. (2014), "in 2010, the highest rate of new HBV infections was among persons age 30 to 39 years (2.33 cases/100,000 population), with males and black persons at highest risk." The USPSTF (LeFevre 2014) stated that "the burden of HBV infection disproportionately affects foreign-born persons from countries with a high prevalence of infection and their unvaccinated offspring, HIV-positive persons, men who have sex with men, and injection drug users." In addition, "persons born in regions with a prevalence of HBV infection of 2% or greater, such as countries in Africa and Asia, the Pacific Islands, and parts of South America, account for 47% to 95% of chronically infected persons in the United States" (LeFevre 2014). "The US death rate for persons with HBV infection in 2010 was an estimated 0.5 per 100 000. The highest death rates occurred in persons aged 55 to 64 years; men; and nonwhite, nonblack persons. Compared with non–HBV-related deaths, HBV-associated mortality is approximately 11 times higher among persons of non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander descent" (LeFevre 2014).

Summary

HBV infection continues to be problematic in the U.S. with both health and societal consequences. Keys to reducing the incidence and prevalence of HBV infections include individual behavioral risk reduction, vaccination and screening. CMS encourages appropriate HBV vaccination. For screening, the USPSTF reviewed the available evidence and provided a B recommendation for screening for HBV infection in asymptomatic, nonpregnant adolescents and adults at increased risk for infection and an A recommendation for all pregnant women. CMS reviewed the USPSTF recommendations and performed its own review of the evidence. The evidence supported that screening for HBV infection in the USPSTF-indicated populations is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability and is appropriate for individuals entitled to Medicare benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B with the assumption that the person receives appropriate post-screening treatment and/or non-pharmaceutical interventions.

Screening for HBV infection provides direct benefit to the Medicare beneficiary. Test results inform the treatment of an existing infection and such treatment can also prevent future health consequences.

CMS proposes the high risk population is best described as persons born in countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection (i.e., ≥ 2%), US-born persons not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (i.e., ≥ 8%), HIV-positive persons, men who have sex with men, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection. In addition, CMS proposes that repeated screening would be appropriate annually only for beneficiaries with continued high risk (i.e., men who have sex with men, injection drug users, household contacts or sexual partners of persons with HBV infection) who do not receive hepatitis B vaccination. CMS also proposes that referral for screening for HBV infection is best ordered by the beneficiary's primary care provider within the context of a primary care setting.

CMS proposes that a FDA approved/cleared test, when used consistent with the FDA approved label, provides a greater likelihood that a potential harm of screening testing, i.e., taking action based on inaccurate screening test results, can be avoided. We further propose that compliance by testing laboratories with CLIA regulatory requirements provides an additional, on-going safeguard for screening test quality. CMS considers these conditions essential to maximize patient safety.

IX. Conclusion

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposes that the evidence is sufficient to conclude that screening for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), consistent with the grade A and B recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of an illness or disability and is appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B, as described below.

Therefore, CMS proposes to cover screening for HBV infection with the appropriate U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved/cleared laboratory tests, used consistent with FDA approved labeling and in compliance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) regulations, when ordered by the beneficiary's primary care physician or practitioner within the context of a primary care setting, and performed by an eligible Medicare provider for these services, for beneficiaries who meet either of the following conditions.